Originally published at medium.com. Rev 2020-08-03

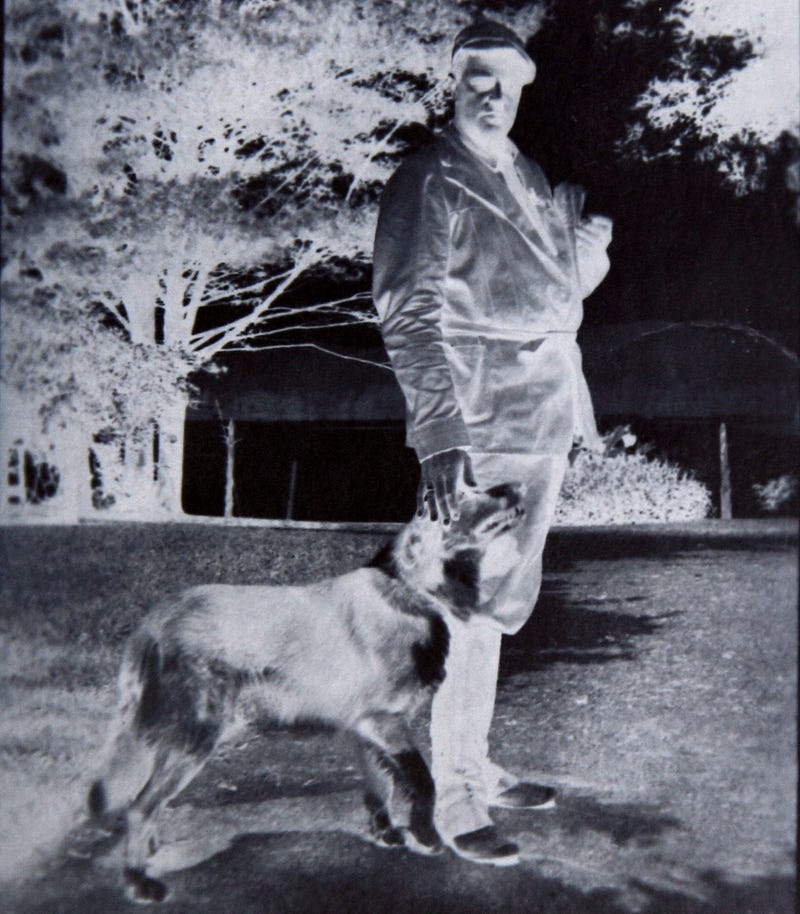

Image:Albert Payson Terhune 1872–1942 collection, Special Collections, The Elihu Burritt Library, Central Connecticut State University, New Britain. Modified: EHB.

* * *

When I started delivering morning newspapers from Al’s step-van, back in 1960, he warned me that early risers, walking their dogs, would startle me. A senior in high school, I wasn’t worried.

I had to be up and ready to go at four-thirty on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Our bundles of papers—the Paterson Morning Call, New York Times, Herald Tribune, Daily News, and Wall Street Journal—waited at a gas station across from the Haledon Diner. After we loaded the bundles, Al drove up the hill toward Wayne, past Paterson State Teachers College (now William Paterson University), while I cut the twine on the bundles and began rolling and rubber-banding the papers.

Al insisted there was a right way to roll and rubber-band the newspapers.

“Wrap a bunch of rubber bands around the middle two fingers of your left hand, then roll up the newspaper—the rubber band will be right where you need it. Pull one off with your right hand and slip it over the paper. Ready to throw.”

The sliding doors of the step-van were always open. The October and early November mornings were chilly. In a few weeks, the mornings would be very cold. About half the time we tossed the papers while the van kept rolling. The rest of the time I did four- or five-house “runs,” dropping the papers at the appropriate spots before returning to the truck. Occasionally I’d encounter an early-morning “apparition” walking his dog.

On the foggy November morning of my birthday, my thoughts were consumed with my driving test, scheduled for later that day. A four-house run took me through the grounds of a Pompton Lakes estate called Sunnybank. A large collie, blue-black, tan and white, rushed to greet me, and a tall, muscular man with a strong jaw materialized in the fog. I reached down to pet the dog.

“Stop.”

I stopped. New chills clutched my back, not caused by the foggy, foggy dew.

“I need to talk to you, Jonathan. I am Albert Payson Terhune.”

The famous author. I had gorged on his collie books—Lad, a Dog and others. Sunnybank had been his home till he died—the year before I was born. Now it was awe and excitement rather than fear that made my heart race.

“Where are your gloves?” he demanded, like he was my father.

I showed him the rubber bands and how I used them.

“Nonsense. When I was a kid we just folded and tucked the paper and threw it. No need for rubber bands.”

When I didn’t reply, he said, “I arranged this meeting because I have a task for you. Seventeen years ago, my former housekeeper was murdered here. The police think it was an accident. You must look up the old newspaper stories and bring the killer to justice.”

“Are you really him?” I blurted, not knowing what else to say. I needed to pet the collie.

“Hard to say if I’m really him, but I am really he,” came the author’s reply.

From three houses away, Al hollered, “Did you get lost or something?”

I turned to go, but Mr. Terhune said, “Wait. I know this is a stretch, but we need to band together to wrap up this case.”

Then there was nothing but empty yard. I raced to finish the run and get back to the truck.

“Did you stop to talk to one of those ghosts I warned you about?”

I did not tell him about my encounter.

The fog of Sunnybank was nothing compared to the fog of school that day. I argued with myself all day long, an argument I couldn’t win:

This didn’t really happen. You’re crazy. Just something you imagined because you love his collie stories.

How could I imagine that? I was wide awake, working and running. I don’t imagine things under those circumstances.

Yes, you do. Your sense of reality is far too elastic.

I couldn’t tell anyone. My parents were rational Calvinists. They would scoff, accusing me of stretching the truth. The next day, taut, with no release, the argument continued:

Nonsense.

No. It did really happen.

You’re going crazy.

No, I’m not—I’m perfectly sane. There’s nothing else strange in my life.

Saturday morning, with rubbery knees, I boarded the brown and tan bus that ran the loop between North Haledon and Paterson. At the main library, I found a biography of Mr. Terhune. After I studied the photos, I decided that if I had seen anyone at all, it had to be him—or “he.”

In the microfiche room I found the boxes with the rolls of film for the 1943 Morning Call and Paterson Evening News already pulled from their drawers. A huge rubber band held them together along with a folded sheet of paper. On it someone had written “November 10, 1943”—the day I was born! I hurried to examine the two items inside the folded sheet. The first was a note telling me to read the Morning Call for November 11, 1943. I loaded the microfiche into the reader and found the date. I scanned the Armistice Day story and read the war updates: U.S. forces in bitter jungle battles on Bougainville in the Solomons; Russian advances against the Germans toward Kiev; talk of the upcoming conference between Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt. All things I had studied in Modern History class and read about in the popular war novels. It was exciting to see what was happening on the day I was born. My father would have been on a ship somewhere in the South Pacific—maybe at Bougainville. I forced myself away from the war news and looked for something about a death at Sunnybank. I knew Mr. Terhune would not be happy by my distraction from duty. I found this story:

Yesterday at Sunnybank in Pompton Lakes, Mrs. Penelope Witherspoon, 49, housekeeper at the estate of the recently deceased author, Albert Payson Terhune, died from a fall down the outside steps leading from her third-floor apartment.

The body was discovered by her husband, Mr. Archibald Witherspoon, 50, as he departed to catch his commuter train into the City, where he works as a manager in the war industry.

“The steps are ridiculously dangerous,” the distraught husband complained to the police, “especially with a heavy frost like this morning. Two full stories of steps straight down from the door.”

The story went on to present additional details and background information. I found the same story in the Evening News, then turned to the second item inside the folded sheet, a note in a feminine hand:

If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well It were done quickly.

Below that, a man had scribbled:

’Tis done, my Lily. Destroy this note immediately. Police suspect nothing. A simple matter of a rubber strap hooked between the balustrades outside the door. I tossed it back into the junk drawer as soon as I heard her fall.

I sat looking at the newspaper story and the note, trying to resolve the discrepancy between newspaper report and fact. I wasn’t going to solve the mystery there, so I jotted down the facts from the newspaper on a sheet from my zipper three-ring binder, those binders that were so popular back in the day, before everyone started using back packs. I slipped the tell-tale note into the side pocket of the binder, careful not to add my fingerprints. After boxing up the microfiche, I left it on the table to be re-filed. I trudged back to City Hall, where I caught the bus home.

I paid even less attention than usual in church on Sunday. Schoolwork suffered for several days while I scoured phone books. Tuesday and Thursday morning I scampered across Sunnybank, grateful to make it back to the truck without getting a tongue-lashing from Mr. Terhune. After school on Thursday I found a Pompton Lakes phone book at the Paterson library. It contained an entry for Archibald Witherspoon. I knew I should go to the police, but I also knew they wouldn’t take me seriously.

Friday I was walking home with my buddy, Faith Van Zyl. We lived a few houses apart and often walked home from Manchester Regional High School together. She was wearing her red and black cheerleader jacket with the zipper hood, the kind of hood that lies flat over the back of the girl’s shoulders when unzipped. Now the hood was zipped up against the cold, framing her brown hair and brown eyes. Eyes that were half worried and half angry when she stopped and challenged me.

“You okay, Jonathan? Why aren’t you telling me what’s bothering you?”

“I’m fine.” I wished I could tell her.

“You’re acting like you’ve seen a ghost.”

“I have,” I blurted out.

She harassed her pop bead bracelet. I knew this was the end of a good friendship. Stupid. At least she wouldn’t blabber it to everyone. I knew her.

“Tell me about it.”

She read the stress in my face.

“Of course I believe you,” she said and pulled me to a bus stop bench. We sat there, oblivious to the cold. I told the story. The police wouldn’t believe me, I complained. Even if the phone number led to the right Archibald Witherspoon, the only evidence was this note provided by a ghost. Sure, handwriting and fingerprint analysis might prove it authentic, but no one would take it seriously enough to do the analysis.

“You need to at least try.”

The driver’s license was in my pocket, but no way would my folks let me take a car to Pompton Lakes.

“I’ll drive you.”

The first thing was to make copies of the note. I didn’t want to risk losing the original to the police. Using Thermo-Fax or Photostat was expensive and I didn’t want other people seeing the note. I hadn’t even heard of Xerox yet. I borrowed a Polaroid camera from a friend’s parent and took two good shots of the note.

Next morning Faith drove me to Pompton Lakes in the dark green ’49 DeSoto her parents let her use. Today, it’s hard to imagine how big those cars were, with their shiny chrome grill and bumpers and their elegantly flared fenders. Faith could drive six of us to “away” games: me (the team manager), two other cheerleaders, and two players, besides herself. No seat belts, of course, and a crazy semi-automatic transmission I could never make sense of. But she drove it well. I usually enjoyed the faint smell of her grandfather’s cigars trapped in the cloth upholstery and headliner. Not today. I made Faith turn off the Top Forty on the radio—just AM. Nineteen-forty-nine car radios were only AM.

At the police station, she waited in the car. It was my story, she insisted, and it would just distract if there were two of us. I got as far as the front door and stopped. Looked back. She gave me thumbs up. I didn’t move. She started the car.

“If you don’t go in, you’ll need to find your own way home.”

The skeptical officer at the desk finally sent me back to a detective.

“Third door on your right.”

I knocked lightly at the open door. The man who swiveled to me in his desk chair seemed as old as my grandfather, but tall and skinny, bald, with a gray fringe. Cigarette ash spotted the lapels of his open, double-breasted suitcoat and his five-inch-wide tie that sported pin-up figures.

“What’s this about a supposed murder at Sunnybank, kid?” he said, studying me with bleary eyes, rocking back in his chair. I stepped into the room. He made no indication that I should sit. I knew I shouldn’t have come.

“No murder.” He brought his chair upright, slammed his fist on the table and aimed his bleary eyes at me. “Accidental fall. I was the investigating detective.”

“I found this note that shows it was murder.”

“Where?”

This was the moment of truth. No way I could tell him about the meeting with one of my favorite authors.

“I came across it at a garage sale.” It sounded ridiculous even to me.

His face got red. He stood, his bleary eyes menacing. “You’re wasting my time. Out of here.”

“At least let me show you—”

“Out of here. We don’t appreciate jokers like you. Scram before I arrest you for making false claims to a police officer.”

I scrammed.

Now what. I wished I could talk to Mr. Terhune. Once I explained how impossible the task was, he would let me off the hook. But it couldn’t be while delivering papers.

“We’ll go up there tonight,” Faith said. “Hopefully he’ll appear.”

What could I tell my parents? That I had to go to Pompton Lakes to talk to a ghost? How could I justify being out all night—or at least till he put in an appearance? It’s not like it was summer and I could claim to be camping on High Mountain.

“No problem,” Faith said. “We’ll say we’re going to the late movie. That’ll give us till at least midnight.”

Going to a movie with Faith would raise eyebrows. I hadn’t ever gone on a date. She and I had often done things together. But in my family’s eyes this would be a step further.

“We could say we were going to see Elmer Gantry,” she said.

“My parents won’t approve Elmer Gantry. How about Please Don’t Eat the Daisies?”

I thought of another problem. “They’ll want to know about the movie and then find out we weren’t really there.”

“We get Patty and Ralph to tell us all about it. They went last night.”

“Sure. And what will Patty and Ralph think we’re doing instead of going to the movie?”

Faith smiled. “Let them think.”

It was dark at six o’clock when we left. We parked in a residential area a half mile from Sunnybank and walked to the estate. The yards and woods were not early-morning friendly. Faith gripped my hand and stayed close. It felt good.

“Where did you see him?”

I guided her to the spot. We sat in a gazebo near the spot, protected a bit from the wind. From across the lake, lights reflected on the water. She snuggled, her hands clutching the front of my jacket. After a few minutes I put my arm around her shoulder. She looked up and smiled.

The collie’s bark came from just outside the gazebo. We jumped when the man emerged from the darkness.

“You two here to avenge a murder or to make out?”

I was glad the darkness covered my blush. I told him I had read the stuff in the library and made the copies of the note. And that I had an address for Archibald Weatherspoon, right there in Pompton Lakes. That the police had thrown me out. That I was stymied.

“Surely, it’s obvious,” he said. Then was quiet and waited.

“We can’t prove anything.”

“What would you do if you were hunting and your dog trapped a rabbit in a burrow?” He waited again.

“I don’t know anything about hunting,” Faith said.

More silence. Then I got it.

“Smoke him out.”

The dog came to me. I got to pet him for just an instant before he and Mr. Terhune vanished. Faith took my hand and pulled me to her till her face was inches from mine. I hesitated. She smiled the most beautiful smile. I didn’t dare kiss her.

“How are we going to smoke out the killer?” she asked after a moment.

We rejected a number of harebrained ideas. Faith came up with the winner. Another half hour and we had the plan.

In the morning I made it to nine o’clock church with my parents, though I dozed during the sermon. After Sunday dinner my family often took rides in the big Country Squire station wagon with the fake wood trim. I begged off, saying I needed a nap after being out late. Faith came over when they were gone. She stood behind me with her arms on my shoulders while I lifted the receiver from the wall phone. I put my index finger in the number seven hole to rotate the dial. The finger slipped from the dial ring before I could complete the arc. I took deep breaths, started over, and managed to get the number dialed.

“Mr. Archibald Witherspoon, please.” I tried to sound mature and keep my new bass voice solid.

“This is Archibald Witherspoon,” came a proper, formal voice. “How may I help you?”

“Archie, I know you murdered Penelope. You’re going to have to—”

“Don’t mess with me, Bobby.” He hung up.

“Who’s Bobby?” Faith asked.

“Has to be someone Witherspoon knows and thinks might know something about the murder.”

Had I blown it? Faith had to leave before we figured out what to do next, since I was supposed to be napping. I was “up” and doing homework by the time my parents returned, not that I could concentrate very well.

In the morning I was about to walk to school when Faith showed up in the DeSoto. She hardly ever drove to school. I climbed into the passenger seat. She shoved the open Morning Call under my nose, pointing to this article:

Mr. Bobby Caruthers, 37, of Little Falls, was found murdered in his apartment late last night.

Mr. Caruthers has recently moved back to the area after living in California since he was discharged from the Navy in 1946. He grew up in Pompton Lakes and graduated from Pompton Lakes High School in 1941.

I reached the same questions Faith had—was this Bobby the same Bobby? Why had Archibald assumed it was Bobby when I called? Was there some connection with Penelope Witherspoon? We had to take another look at the newspaper stories about her death.

We raced downtown in the DeSoto as soon as school was out, hurried to the microfiche room, pulled the 1943 Morning Call, and found the story again. The last paragraph read:

Besides Mr. Witherspoon, Mrs. Witherspoon is survived by her son from a previous marriage, Mr. Bobby Caruthers. Caruthers is now serving the war effort in the United States Navy.

We didn’t say anything on the drive to Faith’s house. Our effort to avenge the first death had caused a second death. This was not a game.

Mrs. Van Zyl made us tea. We took our cups and some almond tarts down to the rec room.

After more silence, Faith said, “So, do we forget about this?”

I wanted to forget about it. We were in over our heads for sure. Then I had a picture of perpetual detention hall with Mr. Terhune sitting up front. I couldn’t forget about it.

“You’re out of it. But I can’t let it go.”

“We’re in this together.” She gave me a hug, and I hugged her back. We heard Mrs. Van Zyl’s car pull out of the garage and drive off.

“Now’s our chance to call him again,” I said.

“Be sure to tell him right off about the note, so he doesn’t hang up.”

The phone was on the end table next to the sofa—a turquoise Princess phone with its streamlined look and lighted dial. I picked up the receiver and dialed the number. Dialing didn’t go any easier this time.

“Mr. Witherspoon, you killed the wrong person. Here’s the deal. I’ve found an old note of yours. I’m thinking it might be valuable to you.”

Silence.

I began reading and got through the Shakespeare quote and “’Tis done, my Lily,” before he stopped me.

“What do you want?”

“I’m thinking this note might be worth a thousand dollars to you.”

“Damn blackmailer!” he screamed.

I said nothing.

A long pause. Then, “OK. When and where?”

I told him.

Tuesday wasn’t too bad, but Wednesday was the longest school day of my life, followed by useless efforts at homework. At dinner, I was so quiet my parents asked if something was wrong. After dinner I grabbed my jacket.

“Where are you going?”

“Out.”

“What are you doing?”

“Nothing.”

“Remember, home by ten. School night.”

“Right.”

Now Faith and I huddled together in the deep darkness beneath the high school football stands. Wind played the wood and steel structure like a monstrous glass harmonica. We strained to hear footsteps over the eerie moans. I kept a grip on her hand; her grip was so tight I could not have freed my hand if I wanted to.

Faith’s brother, Doug the Cop, was close by, in the entranceway to the rest rooms, where we had removed the lightbulb. We hadn’t told him the true story. Only that we found some incriminating letters from someone who thought he was going to meet us to pay the blackmail.

“That’s dangerous,” Doug said. “What if he just shoots you?”

“We said we would take him to the letters after he gives us the money. He can’t shoot us till then. You’ll hear and record what he says and then arrest him.”

Remembering Doug’s warning now didn’t help my nerves.

The appointed time came and went. After a half hour we started to go. A voice stopped us. Mr. Terhune and his collie were faintly visible in the darkness.

“He’s parked out there, waiting for you to leave. Looks like he’s going to follow you.”

Faith gripped me like a python.

“What do we do?” I asked.

“Walk normally to your car. Don’t let on you’re aware he’s there. Doug,”—Doug was standing dumbstruck behind us—“Doug, wait till both cars have driven off. Then go out to your car and tail them.”

Doug stuttered, “Who—whooo aaaare you?”

“They’ll explain later. You lovebirds,” he said to Faith and me, “go up Oakwood Avenue to the very top and pull off onto the trail there, like you’re going to watch the submarine races. He’ll have to be far enough behind so as not to be spotted. That’ll give you time to get out of the car and hide in the woods.”

“What happens after we hide in the woods?” I asked.

“We’ll have to play it by ear.”

The answer was not comforting. I was going to make sure Faith and I were deep in the woods and well-hidden when Mr. Terhune began to play it by ear.

Faith and I were almost to the DeSoto when I heard a car door open. Then footsteps and Witherspoon said, “Stop there. Don’t try anything. I’ve got a gun.”

I turned, pushing Faith behind me.

“You’re late,” I said. “We waited for you.”

“Do you think I was about to walk into whatever trap you had laid for me? Now give me the note. And forget about the money. You won’t be needing that.” He came close and reached out his hand. From behind him, Doug approached silently on his crepe soles. Would he be able to get close enough to apprehend Witherspoon without someone getting shot? Most likely me.

Then Mr. Terhune appeared between me and Witherspoon.

“Archie,” he said, sadly, as he removed the gun from the hand paralyzed with shock.

“Albert?” came the weak whisper.

“Why did you do it, Archie?”

I could smell the urine trickling down his pant leg. A weak voice pleaded, “I had to, Albert. You know that. She was a bitch.”

Mr. Terhune stuck the gun in his pocket. He placed a hand under Witherspoon’s arm to keep him from falling, which further weakened Witherspoon’s control. By now, Doug had crept close.

“That’s not true, Archie. She was a lovely woman. But you wanted Lily. It was a dirty, evil act to satisfy your lust. That’s why you did it, Archie.”

“Fine. No court’s going to believe a ghost anyway.” He seemed to recover some vitality. “I’ve had seventeen great years with Lily. Good years that we both deserved. Penelope got what she deserved for trapping me into marrying her.”

“And then you killed Bobby, your step-son.”

“That was a mistake. I thought he was the blackmailer.”

Doug placed his hand on Witherspoon’s shoulder. “Archibald Witherspoon, you’re under arrest for the murders of Penelope Witherspoon and Bobby Caruthers.” He cuffed Witherspoon. The collie licked my hand and barked, then vanished in mid-bark along with Mr. Terhune. The gun lay on the ground where my hero had stood.

Witherspoon could not move. Doug had to support him to the cruiser.

When I reached in my pocket for the incriminating note, it was not there. Just a bunch of rubber bands. I guess, since Doug and Faith and I had all heard Witherspoon’s confession, Mr. Terhune knew the note wasn’t going to be needed. But then I wondered. Had it ever “really” existed? Why hadn’t Doug the Cop seen Mr. Terhune?

The next morning, Al was cutting open a bundle of Morning Calls when he waved one at me, spilling his coffee (no cup holders in those days) and his bag of rubber bands. My name and Faith’s name under the headline about the murder at Sunnybank! No mention of Albert Payson Terhune’s intervention. I had told the police the cockamamie story about finding the note at a garage sale, and that I had lost it in the evening’s struggle. Stretched the truth a bit.